Worldbuilding can be an intimidating part of writing science fiction/fantasy, whether it’s an epic fantasy or a distant far-future space opera.

Worldbuilding can be an intimidating part of writing science fiction/fantasy, whether it’s an epic fantasy or a distant far-future space opera.

There are many ways focusing on worldbuilding first can go awry, chief among them the possibility that worldbuilding becomes such a focus that the writer never moves on to the writing.

If you want to strike a balance between strong worldbuilding and not getting bogged down, here are some tips from my decade of experience writing novels and degrees in Folklore and Mythology before that.

Culture is made out of small pieces and big pieces. And most of the big pieces are made out of small pieces. How people greet one another is a part of power dynamics. Formality, gendered language, social context, and more.

Thinking about everyday life can be a great way to start creating the small pieces that will make up the big piece OR small pieces that reinforce the big ideas you’ve already created. If you have a culture that worships a benevolent sun god, think about how little things in daily life reflects that practice. They’re likely to see the daytime as the time of goodness. Which may mean that breakfast and lunch are framed as more important meals because they’re done under the watchful eye of the sun. Or maybe weddings are always conducted in the morning to represent rebirth alongside the sunrise.

Few cultural elements are created in a vacuum. Folklore about medical practice likely developed alongside folklore about agricultural practice. How are they interconnected? How do the hero legends of the culture reflect its ideas about what heroism means and what important technologies/blessings the culture needed to become who they are?

The Greeks tell the story of Prometheus stealing fire from the gods and giving it to humanity””an essential blessing. But they also tell of Prometheus facing eternal punishment for that theft. What does that say about how the ancient Greeks viewed humanity’s relationship with the gods?

Thinking about what elements of culture should resonate with one another and which elements make sense to be in tension can help develop a world that feels real.

One of the best pieces of advice about worldbuilding that I can give you is to think about power. Who has power, who doesn’t, how people navigate the systems of power to achieve what they want when they have access to power and especially when they do not.

It makes sense when worldbuilding to think about what groups within a nation or culture have greater access to power and which are excluded from holding or wielding power. And there’s a good chance that not all of the types of power are wielded by the exact same group. So sometimes you’ll have a character that has access to some power but is disempowered along another axis. An influential member of a minority/marginalized religion. A superhuman on the run from the law in a society where superpowers are outlawed. A male anti-imperial freedom fighter in a patriarchal society.

It makes sense when worldbuilding to think about what groups within a nation or culture have greater access to power and which are excluded from holding or wielding power. And there’s a good chance that not all of the types of power are wielded by the exact same group. So sometimes you’ll have a character that has access to some power but is disempowered along another axis. An influential member of a minority/marginalized religion. A superhuman on the run from the law in a society where superpowers are outlawed. A male anti-imperial freedom fighter in a patriarchal society.

Characters like these can display the tangled, interesting, and scary interconnectedness and tensions between systems of power, and a story can show how these interactions play out in material ways””how people can and cannot navigate through social systems and access to resources (material, social, etc.).

I think it’s okay for a first draft to be really messy, to include contradictions and continuity errors. Editing is a really good time to put all your worldbuilding affairs in order. It’s possible to bake in a fundamental flaw to a work if you make a big enough mistake in the first draft, but for the textual worldbuilding””names of places, material culture that doesn’t serve as the backbone of the plot, the local festival going on while the characters visit the city””all of that is well within the range of things that can be reconciled and corrected in the editing stages of working on a novel.

When in doubt, set yourself up with more tools before you even begin. Read fiction set in real-world cultures written from an insider’s point of view or from that of a well-researched, respectful outsider. Read histories and books on mythology, folklore, linguistics, architecture, and more. Learn to see the choices made in fictional worldbuilding that would otherwise go unnoticed as “the default.”

The more you grew up with your identity centered by majority culture (in the USA that’s white, Christian, straight, cisgender, middle or upper class, etc.), the more important it is to cast your attention more widely and to escape the default thinking that presents the USA or the UK or other global colonial powers as the protagonists of history.

Another way to put this””if you’re designing an element of worldbuilding, it’s easier to do so when you already know ten different cultures’ analog of that element than if you only know three.

The wider your view of the world and the myriad ways that people live in it, the better-prepared you’ll be to apply that pattern recognition through extrapolation and interpolation with your own work. This is the work of a lifetime, but it’s worth doing, and not just to improve your writing.

As someone who studied world cultures and how to study cultures, I definitely get the impulse to spend a lot of time rounding out a bunch of details and laying a ton of groundwork.

But I’ve found that my desire to write and finish books has pushed me toward less exhaustive prep and more toward improvising in the moment, relying on my training and my judgment, and in the fact that I can come back and make sense of things later if I really need to.

Everyone’s process is different, but if you find yourself wishing you could spend a bit less time on worldbuilding before you start your draft, I hope these tips will be of use.

Bio: Michael R. Underwood is the author of over a dozen books across several series. His latest book is Annihilation Aria. Mike lives in Baltimore with his wife and their dog. He is a co-host on the actual play show Speculate and a guest host on The Skiffy & Fanty Show.

Bio: Michael R. Underwood is the author of over a dozen books across several series. His latest book is Annihilation Aria. Mike lives in Baltimore with his wife and their dog. He is a co-host on the actual play show Speculate and a guest host on The Skiffy & Fanty Show.

Find him online on his website, Twitter, and Patreon.

Buy Links for Aria:

If you’re an author or other fantasy and science fiction creative, and want to do a guest blog post, please check out the guest blog post guidelines. Or if you’re looking for community from other F&SF writers, sign up for the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers Critclub!

...

…only to be proven wrong, of course. A week or so ago at the Surrey International Writers Conference I was absolutely delighted when an audience member hit me with a new one that I hadn’t considered at all.

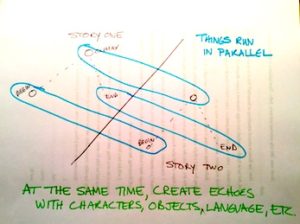

When I teach the class, which focuses on how to take an idea and use it to finish a story, I talk a little bit about story structure and writing process, but most of the class relies on asking participants what the idea is that they’re working with. This time, a woman said, “My idea is a twinned story” and explained that she wanted to write two stories in parallel.

You might argue that it’s a particular manifestation of a frame story, which is something covered in the Devices section of the class, but she wanted it to be more than that: her story was about a couple discovering letters in their attic that tell the story of another couple’s marriage. So let’s look at this according to the structure I use in Moving from Idea to Finished Draft, looking at what it is, what it gives you, what considerations you should take into account while writing, possible pitfalls, next steps, and a few exercises designed to increase understanding of the idea.

...

Video! Please like it or share it if you enjoy it.

...

Want access to a lively community of writers and readers, free writing classes, co-working sessions, special speakers, weekly writing games, random pictures and MORE for as little as $2? Check out Cat’s Patreon campaign.

"(On the writing F&SF workshop) Wanted to crow and say thanks: the first story I wrote after taking your class was my very first sale. Coincidence? nah….thanks so much."

(science fiction, short story) Shi was currently female. She had chosen to present as an eleven-year-old girl, a slim, short shape that she had found disarmed most older people. Although there was a small percentage who found it off-putting. “Creepy,” one had called it, trying to explain the aversion. “An adult mind in a kid’s body? You just know too much.”

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. This site is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.