Literature is the best medium for horror, and comics are the worst. Literature succeeds because of the power of words to suggest, to take you ninety percent there, and leave that final ten percent up to you. The horror we imagine in the darkness of our minds far exceeds anything that can be set down on paper in words or pictures. We love horror because it allows us to exorcise our fears in a safe and fun manner. It usually delivers a moral epiphany, as Mary Shelley intended.

Literature is the best medium for horror, and comics are the worst. Literature succeeds because of the power of words to suggest, to take you ninety percent there, and leave that final ten percent up to you. The horror we imagine in the darkness of our minds far exceeds anything that can be set down on paper in words or pictures. We love horror because it allows us to exorcise our fears in a safe and fun manner. It usually delivers a moral epiphany, as Mary Shelley intended.

There’s also existential horror with no good guys or bad guys, like The Devil’s Rejects. Without a moral epiphany no film can hope to reach a wider audience. Exorcist is not only the scariest movie ever made, it’s one of the most moral.

But enough about that. We’re talking scares. Movies do horror well as they control not only pacing, but every aspect of the experience. They can manipulate what you see — or what you think you see –on the screen. They can scare the bejesus out of you with sudden motion, unexpected thrusts from unexpected places. These tropes prove irresistible to hack filmmakers who fill their film with ominous musical crescendos and fake scares. Which brings us to pacing. You want to catch your audience off-balance; that’s why you throw in the fake scare followed a split-second later with the real scare.

Comics can’t do that. They must rely on the storytelling alone for inevitably, when the big scene comes — the full-page panel of the werewolf or the witch or the monster — it’s just a drawing on paper. Sure, there have been some horrible drawings in comics –pictures of torture or mutilation — but is this really horror? Or is it just Grand Guignol? You set the comic down and it goes away.

Horror is an intimate, terrifying sensation. It’s far more than disgust, and you all know what I’m talking about. You can count on the fingers of one hand those movies that touch on real supernatural evil. They’re the ones you remember.

Why are horror comics so popular?

People love the genre and the whiff of cheese issuing from the sideshow exhibit. The great EC tales in Shock Suspenstories, Tales from the Crypt and their ilk create horror by leaving the protagonist in a horrible situation. Buried alive. Chained to a corpse in a desert. As children, we can all relate because we can all imagine ourselves in that situation. The best comic book horror succeeds through powerful storytelling and great characterization. Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing or even Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, like the time Abner was trapped in the mushroom cave with no hope of rescue. We experience a visceral horror through the protagonist because we care about him, her, or it. It’s not the same jolt as in the George C. Scott movie The Changeling when that ball comes bounding down the stairs.

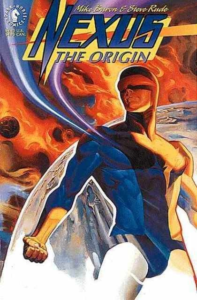

In Nexus, Steve Rude and I are always trying to put our finger on the pulse of evil. But true horror depends on the unknowable — and we don’t know the unknowable. So how can we show it? The best we can do is dance around the edges and try to capture aspects of evil that ring true.

In comics, as in life, the true horror lurks just beyond our senses.

BIO:Mike Baron broke into comics in 1981 with Nexus, his groundbreaking science fiction title co-created with illustrator Steve Rude; the series garnered numerous honors, including Eisners for both creators. A prolific creator, Mike is responsible for The Badger,Ginger Fox, Spyke, Feud, and many other comic book titles. Baron has also written numerous mainstream characters, most notably DC’s The Flash, Marvel’s The Punisher, and several Star Wars adaptations for Dark Horse. He lives in Colorado with his wife, dog, cat, and wildebeest.

BIO:Mike Baron broke into comics in 1981 with Nexus, his groundbreaking science fiction title co-created with illustrator Steve Rude; the series garnered numerous honors, including Eisners for both creators. A prolific creator, Mike is responsible for The Badger,Ginger Fox, Spyke, Feud, and many other comic book titles. Baron has also written numerous mainstream characters, most notably DC’s The Flash, Marvel’s The Punisher, and several Star Wars adaptations for Dark Horse. He lives in Colorado with his wife, dog, cat, and wildebeest.

Find out more at Mike’s website www.bloodyredbaron.com or on Twitter @BloodyRedBaron.

If you’re an author or other fantasy and science fiction creative, and want to do a guest blog post, please check out the guest blog post guidelines. Or if you’re looking for community from other F&SF writers, sign up for the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers Critclub!