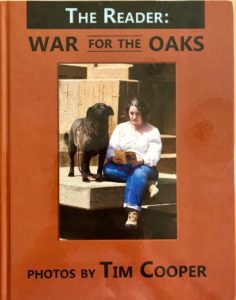

The Reader: War For The Oaks is a hardbound book presenting a photography project by Tim Cooper. It’s a slim little 8.5″³x 11″³ volume, clocking in at 96 pages. The pleasant interior design presents the photos nicely, along with some pretty arboreal details. The cover, whose design is unobjectionable but unremarkable, features a photo that lets the reader know exactly what the book is about: photos of people reading War For the Oaks in various Minneapolis locations.

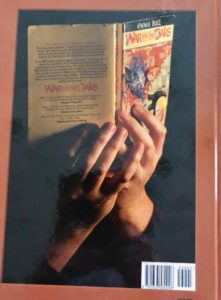

There are a few books I have re-read so many times that they are an integral part of fantasy to me, and Emma Bull’s first novel, War for the Oaks is one of them, featuring Eddi McCandrey and her half-human, half-elvish band, the Fey. It was originally published in 1987; the paperback copy I’ve been carrying around for decades is battered and coverless now, but it was a pleasure to have the task of going back and reading it yet again in order to do this review.

I’m not alone in loving this story, and the book’s part in defining and shaping urban fantasy cannot be overestimated. Reading in many ways like a crisper, less Romantic version of Charles de Lint, Bull demonstrates in this book that despite being one of the quieter writers, she will become a major talent. Many nifty but commercially non-viable projects that we would miss if reliant only on traditional publishing have come out in recent years, often supported through crowdfunding; this one was a Kickstarter project. It’s delightful to see a project dedicated to the novel in this way, celebrating how much the book has meant to many readers.

Which is perhaps my major caveat. This book will enchant, down to their very toes and beyond, those who love Bull’s novel and know the city as well. Cooper’s photos show locations from the book in an order corresponding to the novel’s chronology, each time with people reading War for the Oaks somewhere in the picture. For someone who loves the book in part because of its setting, the sole disappointment may be that the photo are low enough resolution that sometimes it is difficult to make everything out.

Familiar with the book but not so much with the city? Mileage will vary here, depending both on one’s degree of affection for the book as well as how firmly the reader is attached to their vision of things. Someone with a mental vision that is particularly strong, in fact, might find it jarring to have it contradicted by these pictures.

Familiar only with the city? Here again mileage will vary radically depending on factors like how interested one is in examples of projects like this or if one is a book collector specializing in fantasy and science fiction (in which case, you’ve probably had the novel on your list but just never got around to it). Lovely extra details scatter themselves here and there throughout the book, as well as photos featuring other authors like Elizabeth Bear, Stephen Brust, PamelaDean, Marissa Lingen, Scott Lynch, and Patricia C. Wrede. Essays by Dean, Sigrid Ellis, Sarah Olsen and Katherine St. Asaph appear at the back, along with a poem by Alec Austin.

Familiar only with the city? Here again mileage will vary radically depending on factors like how interested one is in examples of projects like this or if one is a book collector specializing in fantasy and science fiction (in which case, you’ve probably had the novel on your list but just never got around to it). Lovely extra details scatter themselves here and there throughout the book, as well as photos featuring other authors like Elizabeth Bear, Stephen Brust, PamelaDean, Marissa Lingen, Scott Lynch, and Patricia C. Wrede. Essays by Dean, Sigrid Ellis, Sarah Olsen and Katherine St. Asaph appear at the back, along with a poem by Alec Austin.

I’ve stuck this on one of my shelves of favorite F&SF next to that battered paperback copy of War for the Oaks, because it’s definitely a keeper. Next time I’m at a con with the author, I may even take it along, because having it signed by the person whose book inspired so much passion would make it even niftier.

(Tired Tapir Press, 2014)

You can read this review at http://thegreenmanreview.com/books/recent-reading-eddi-and-the-feys-revival-tour/

It’s always bothered me that fantasy and science fiction get lumped together into a single category. The two genres seem very different, at least on the surface. Fantasy usually features some kind of magic as a core speculative element. It often takes place in a secondary world at a pre-industrial state of technology. Science fiction, in contrast, usually takes us to the future in which some as-yet-nonexistent technology underlies the plot. Granted, there’s a huge overlap between fantasy and science fiction fandoms. Maybe that means we live for escapism, whether to a fantasy world or outer space.

It’s always bothered me that fantasy and science fiction get lumped together into a single category. The two genres seem very different, at least on the surface. Fantasy usually features some kind of magic as a core speculative element. It often takes place in a secondary world at a pre-industrial state of technology. Science fiction, in contrast, usually takes us to the future in which some as-yet-nonexistent technology underlies the plot. Granted, there’s a huge overlap between fantasy and science fiction fandoms. Maybe that means we live for escapism, whether to a fantasy world or outer space.