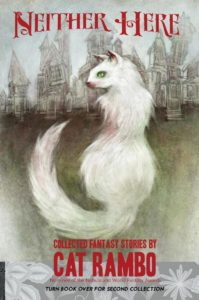

Here’s something from the current piece. For fellow West Seattleites, the coffee shop in question is indeed the Admiral Bird. This is a sequel to “The Wizards of West Seattle,” which is available in Neither Here Nor There, just out this week!

Here’s something from the current piece. For fellow West Seattleites, the coffee shop in question is indeed the Admiral Bird. This is a sequel to “The Wizards of West Seattle,” which is available in Neither Here Nor There, just out this week!

“You need to stop holding a grudge about it,” Penny said.

Albert snorted. “You tried to kill me!”

“I’m a demon. That’s my nature. And it was one of the old lady’s tests. You don’t need to worry about me any more.”

Albert didn’t say anything, but he was unconvinced. In the months since he’d become apprentice to May Huang, one of the wizards of West Seattle, he’d faced several tests, but none as harrowing as that long chase down Alaska Way towards Alki with a long-faced and eager Penny on his heels. Only his encounter and subsequent alliance with Mr. Gray had put a stop to that, and Albert was still unsure what the consequences of that would be.

Penny mocked him. She manifested as a bright-eyed woman of indeterminate age, her face sharp-featured. “Oh, Penny, you’re so scary, oh Penny I can never unsee what I have seen, oh Penny please don’t eat my soul.”

“I’m unclear why don’t eat my soul is an unreasonable demand.”

“I’m just saying, you don’t need to worry about it. Anyhow, Huang wants me to teach you about oracles.”

They were walking down California Ave, passing the Admiral Theater. They both saluted the Little Free Library there, Penny with a graceful curtsey, Albert’s bow slightly more awkward, as they passed.

“I know how oracles work,” Albert said smugly. “That’s how I knew you were something other than human. I found the Oracle, left a crayon in his path.”

“He’s powerful because of the limitations on his magic,” Penny said. “Being able to use only found objects is pretty severe. But there are other routes.” She pointed. “We’re headed to the Bird. I need coffee.”

“Isn’t that a flower shop?”

“And here you have a principle of oracles. Anywhere boundaries blur, they can manifest.”

He’d passed the store a hundred times on walks and seen the flower shop sign, but closer inspection proved the front was a coffee shop, shifting into flowers in the back as seamlessly as two interior shots Photoshopped together.

At the counter Penny ordered coffee but Albert shook his head when she glanced at him. She shrugged. He looked around: dinette tables and chairs, an old truck serving as coffee table, pictures on the wall, the frames the size of his hand, enclosing stamp-sized pictures. He went closer to look.

Each was a scene from West Seattle: the shore at Lincoln Park, the overlook near Huang’s house, the playground at Hiawatha, drawn in fine-nibbed pen and colored in jewel-colored inks that made each one, a summer’s day, come alive. They were as bright and lovely as the day outside, and he craved one of them instantly.

A little label by the cluster said, “Enquire at the register about the price.” He went back to where Penny was counting out her bills.

He waited till she was done and asked the woman at the counter, “Excuse me, how much are the pictures?”

She tilted her head, considering him. He was suddenly conscious of the smear of yogurt from this morning’s breakfast on the knee of his jeans, the fact that he hadn’t bothered to shave, and his “Uncle Ike’s Pot Shop” t-shirt.

Let me know what you think! Patreon supporters, you get to be the first ones to see the finished version. 😉

Enjoy this sample of Cat’s writing and want more of it on a weekly basis, along with insights into process, recipes, photos of Taco Cat, chances to ask Cat (or Taco) questions, discounts on and news of new classes, and more? Support her on Patreon..